Bed-sharing is the habit or custom of parents and infants sharing the same bed. It is practiced in many different cultures to build family closeness, and, sometimes, bed-sharing is practiced out of economic necessity. However, in the United States bed-sharing is not recommended by pediatricians and other healthcare professionals. While the American Academy of Pediatrics advises that parents avoid bed-sharing for a baby’s first year of life to reduce risk of sudden infant death syndrome (Ben-Joseph, 2022), they offer no official sleep guidelines for children of toddler and preschool age (e.g., 1 to 6 years old). Research, to date, is also ambiguous on the physical and psychological effects of bed-sharing with toddler and preschool-aged children (Covington et al., 2019). As a parent, if you make the decision to begin by having your child sleep in their own bed or you decide to transition your child to their own bed after they have shared your bed, you may find it useful to understand your child’s motivations for climbing into your bed and identify tools to help your child confidently sleep on their own.

The differences among co-sleeping, bed-sharing, and room-sharing

Co-sleeping is a term that refers to parents and children sleeping in close proximity to one another (Ben-Joseph, 2022). You can co-sleep with your child when you share a physical space with your child during sleep time (e.g., bed, couch, chair) or when they sleep nearby in your general area (e.g., the crib is in your room).

Bed-sharing and room-sharing are two forms of co-sleeping that are described in the following ways:

- Bed-sharing is a form of co-sleeping that occurs when your child shares the same bed with you and/or another parent/caregiver (Ben-Joseph, 2022).

- Room-sharing is a form of co-sleeping that occurs when your child sleeps near your bed, usually in a crib, play yard, bassinet, or bedside sleeper (Ben-Joseph, 2022).

Reasons you and your family may consider bed-sharing

As a parent, your family may consider bed-sharing for one of the following social-emotional, safety, cultural, or financial reasons.

- It alleviates the child’s separation anxiety.

- It helps the child cope with nightmares.

- It fulfills emotional needs for parent and/or child.

- It helps the parent monitor the child’s safety throughout the night.

- It calms the child’s fear of a dark room.

- It supports the child if there is too much light in their room.

- It respects and honors the family’s cultural norms.

- It serves families who have few available beds.

- It helps keep the child warm if the home has poor heating quality.

- It centralizes the cool areas of the home if the home as poor cooling quality.

The effects of bed-sharing on families

As noted above, there are many reasons that you and your family may consider bed-sharing. However, as a parent, you should be aware of the potential effects—negative and positive—that bed-sharing can have on you, your child, and your family.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

|

|

Tips to Get Your Child to Sleep Alone

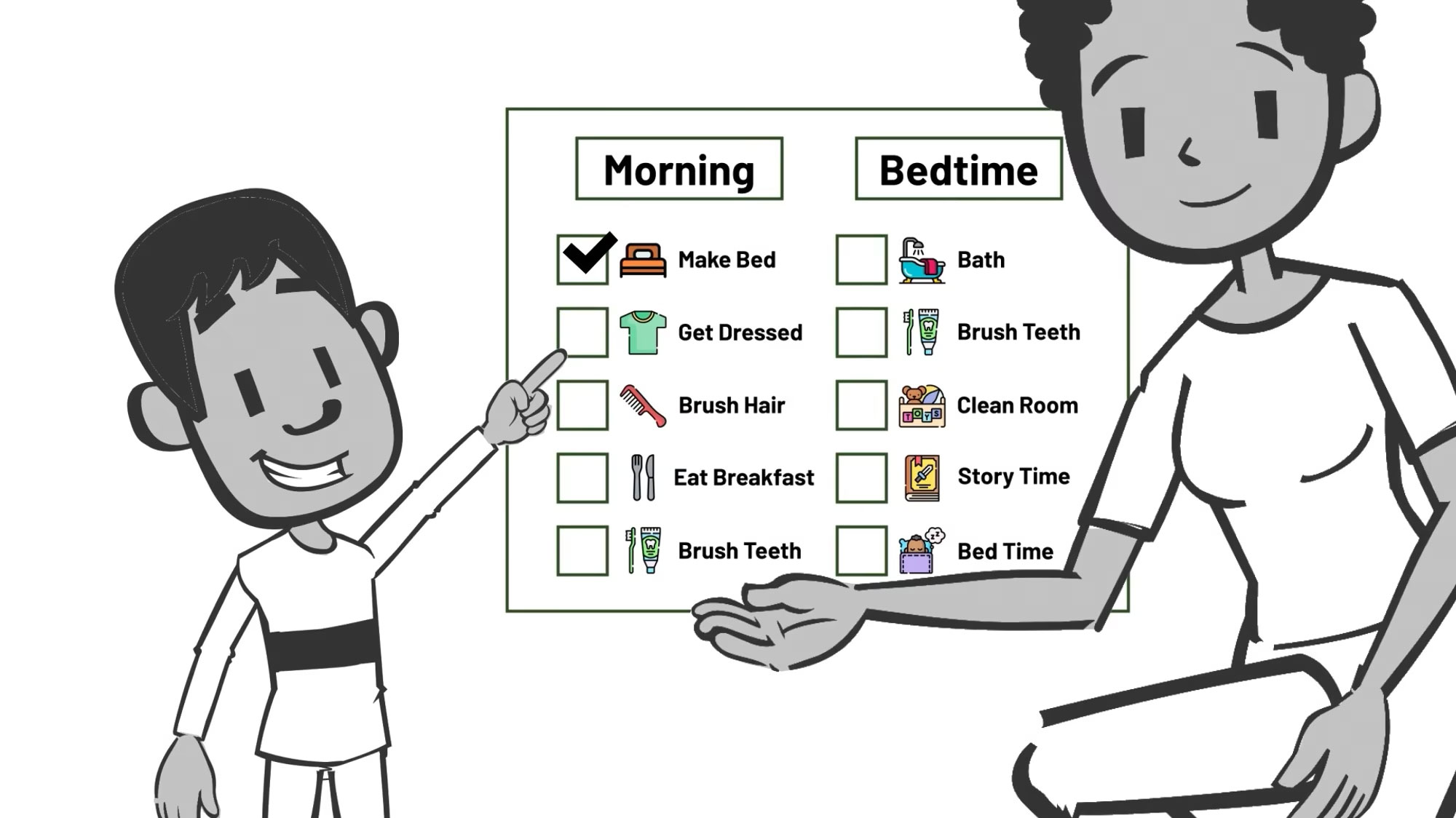

Children are natural explorers, and they often test limits. Therefore, you will probably want to set guidelines and expectations for your child at an early age. This includes establishing a bedtime routine. Consider the following tips to help your child develop healthy sleep habits and proper sleep hygiene.

- Establish a bedtime routine. Ensure your child can form positive associations with sleep by establishing a predictable bedtime routine. You may begin with a warm bath and follow up with brushing and flossing your child’s teeth. You may relax with a bedtime story or a quiet song before putting the child into their own bed. Remember, avoid electronics and screen time for at least 1 hour before bedtime. Blue-light exposure from these devices can keep the child awake as it can trick the child’s brain into thinking it is daytime, and the child’s brain stops releasing melatonin, which is a sleep hormone (McCarthy, 2022).

- Coordinate a plan and stay consistent. You can help your child feel in control of their actions when you talk through the bedtime plan with them early in, or throughout, the day. Together, you and your child can determine what to expect, mentally prepare to implement the plan, and get excited about your child showing you how they can sleep in their own bed. When it’s time for bed, revisit the plan with your child, and follow through with the established steps. After you implement the plan, be mindful not to use sleeping in your bed as a reward or a comfort mechanism. For instance, if your child successfully sleeps in their bed throughout the night for 5 nights in a row, you should not relax your expectations on the 6th night. This may confuse your child, and they may believe that sleeping in your bed is still an option.

If your family has decided it is time for your child to begin sleeping alone in their own room, remember it may take some time to reach success. For safety reasons, do not lock your child in their room or lock them out of your room (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, n.d.). However, you may consider one of the following methods to smooth the transition.

- Make a gradual transition. Your child may learn to fall asleep without you if you increase the time that you are outside of their room. Consider putting your child to sleep in their bed when they become drowsy and, then, leave the room. Remain outside the room for 3 minutes before returning to check on the child. Over the next few days, increase your time outside of the room to 5 minutes, then 10 minutes, and continue until your child learns to fall asleep without you.

- Use the chair method. Sometimes, it helps the child to know that you are nearby even if you are not always present. To support your child’s needs, consider gradually decreasing your proximity to the child while you are in their room. For the first night, you may lie on the floor next to your child until they fall asleep. A few days later, you may move from the floor to sitting in a chair next to the bed until your child falls asleep. Continue to increase the distance between the chair and your child, while they fall asleep, until you are sitting by the door and, then, outside the closed door.

- Take 100 walks. Some children may begin the night in their own bed but wake up frequently and get in your bed. Other children may follow you out the door immediately after you tuck them in bed. Consider keeping a neutral reaction and walking your little drifter back to their bed every time they escape. Although it may be exhausting, continue to walk your child to their bed, tuck them back in, and leave the room each time this happens until they are confident with staying in their room all night.

- Develop a reward system. Many children like to see a concrete tool to help support their learning and progress. Consider posting a sticker chart on the child’s wall. With each day that your child remains in their bed, your child can get a sticker (or whatever your family decides to use to positively reinforce your child’s behavior). At the end of the week, if your child has completed their goal, then, they can receive a small prize. The prize can be a new toy, their favorite activity, a trip to the zoo, or a special treat, like praise, attention, and hugs (note, healthcare professionals recommend that food should not be used as a reward). A similar option could be using a piggy bank. Put a set amount of money in the child’s piggy bank when your child sleeps in their bed. At the end of the week, they can use the accumulated money to select a gift of their choice.

- Offer your child a bedtime pass. Your child may be full of the “I wants” at bedtime. They may wake consistently and ask for more water, one more snack, one more story, or one more hug. With a bedtime pass, your child is given one pass to leave their room. The bedtime pass is a visible tool that your child can hold and use to help them learn and understand rules and limits. It also gives your child a sense of control as they learn to respect boundaries.

- Surround the child with some of their favorite toys or items. Work with your child to create a space that is appealing to them. Invite them to help you decorate their room in ways that are exciting and familiar to them. You may bring in your child’s favorite toys and comfort items of their choosing. In addition, you can place photos, books, blankets, and other familiar objects in your child’s room.

- Use a safety gate. Ask your child to stay in bed and to not leave their room. Let them know if they leave the room, you will have to install the safety gate. Follow through with setting up the safety gate if your child exits their room. However, ensure that you keep your bedroom door open so your child knows that you are not far away. This may not be the best option if your child has shown an ability to climb over a safety gate or open it on their own.

- Incorporate a wake clock. As your child develops their understanding of numbers and time, they may appreciate an “okay to wake clock.” Show your child the visual cues they can look for on the clock (e.g., a set time, a color pattern). If they wake before the appropriate visual cue, you can tell your child that they can return to sleep, or they can play quietly in their room until it is time to “wake up.”

Additional Resources

- The Big Bed by Bunmi Laditan

- I Sleep in a Big Bed by Maria van Lieshout

- I Sleep in my Big Bed by Jim Harbison and Little Grasshopper Books

- Sleep in Your Big Kid Bed by Amanda Hembrow

- A Bed of Your Own by Mij Kelly and Mary McQuillan

- It’s Time to Sleep in Your Own Bed by Lawrence Shapiro

- Benny Goes to Bed by Himself by Dr. Jonathan Kushnir and Ram Kushnir

- The Girl Who Got Out of Bed by Betsy Childs

References

Boweman, M., (2017). Reclaim your bedroom: How to get your kids to sleep in their bed. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2017/03/07/reclaim-your-bedroom-how-get-your-kids-sleep-their-bed/98798814/

Children’sHealth. (n.d.). Should I be co-sleeping with my child? https://www.childrens.com/health-wellness/should-i-be-co-sleeping-with-my-child

Children’s Hospital Colorado. (n.d.). How to get kids to fall (and stay) asleep. https://www.childrenscolorado.org/conditions-and-advice/parenting/parenting-articles/get-kids-fall-asleep/

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (n.d.). Healthy sleep habits. https://www.chop.edu/primary-care/healthy-sleep-habits

Covington, L. B., Armstrong, B., & Black, M. M. (2019, July 24). Bed sharing in toddlerhood: Choice versus necessity and provider guidelines. Global Pediatric Health. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2333794X19843929

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2023, January 14). Child sleep: Put preschool bedtime problems to rest. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/childrens-health/in-depth/child-sleep/art-20044338

McCarthy, C. (2022, November 21). How to help your preschooler sleep alone. Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/how-to-help-your-preschooler-sleep-alone-202211212853